TRIBUTE TO CHAIM KOPPELMAN

May 27, 2010

By Dorothy Koppelman

I will begin at the beginning. The first time I saw Hi Koppelman was in 1941, when I visited a studio on 15th Street and there he was sitting at an easel, doing a drawing of a young woman. I have a camera-vivid image in my mind. He was so absorbed, so careful; I knew this was the kind of life I wanted, and I wanted to be close to a man like that.

In February of last year we celebrated 67 years of marriage, and yet strangely perhaps, I have seen even more in the past almost six months since Hi died of why I loved him, why I respect him as an artist—a great artist—a stalwart lover of truth, and an intensely ethical human being.

Each of my early memories has to do with the course of our lives, of the meaning of Chaim Koppelman. The first is about the summer of 1942 when many young artists were working in a lot on Rivington Street making floats for the Win the War Parade.

Hi was against fascism, passionate and imaginative, and I learned from him. I invited him to visit me in Paradise Alley on East 11th Street where I had gone to escape Brooklyn—a Brooklyn which Hi loved and did many works about. I changed about that too.

As Hi and I talked, he told me he felt the great conflict artists had been struggling with was their desire to do “art for art’s sake” as it has been called, and the need to do work that had a message. Social Realism was the style then. But Hi saw himself as a classical artist, and he was troubled about the idea of art as propaganda only.

And then, in that spring of 1942, at a meeting of artists, I was impressed when I heard Hi say that he learned something about art from the poet Eli Siegel which he had never heard before, and that he felt it was important to have a poet on a panel of visual artists speaking about the role of art in society now. Eli Siegel was invited, and Hi designed the poster to tell people about the panel discussion. The date was May 27th, Wednesday, 8 P.M., 1942.

“All Art Is For Life”

I came to that event and what I heard changed my life. Eli Siegel talked about the meaning of art, of how art is about what reality itself is all the time—a relation of opposites. I remember him holding out his hand with the palm open, and then closed in a fist, and showing it was one hand. The same hand can welcome and also can fight, can be both soft and hard, he said, and the artist’s great job is to show that duality in oneness. All art, he said, is against narrowness and for people. Mr. Siegel’s logic, his conviction, the sincerity and force I saw, went into my heart. Chaim and I heard Mr. Siegel say: “When art is good aesthetically, it is good ethically.” And—as he would write: “There is no true difference between the beautiful and the real.” It was that revolutionary philosophic idea that many years later made for the exhibition at the Terrain, “All Art Is For Life and Against the War in Vietnam.”

In the fall of 1942, I joined Hi in studying poetry with Mr. Siegel at 67 Jane Street.

ELI SIEGEL in his library at 67 Jane Street. Photo by Louis Dienes.

Then, on November 11th, Hi was inducted into the army, and that night at the Poetry Group, he wrote lines which Mr. Siegel said were a true poem. It is called “The Boys from Williamsburg”:

In February of 1943, Hi and I were married. In the three years of WWII as Hi was overseas, he was sustained, encouraged and educated by his correspondence with Mr. Siegel. Some of the beautiful drawings Hi sent me in his letters are in this exhibition.

Early drawing, c. 1944, done in France.

Our lives, the high times and the rough times, are intertwined with the history of Aesthetic Realism. We were studying, in detail, the meaning of the principle: “The resolution of conflict in self is like the making one of opposites in art.” We were seeing the whole outside world differently.

These are some memories that can also tell what kind of person Hi was—the person you could enjoy spending time with. Hi was very funny—

KOPPELMAN (second from left) striking a humorous Napoleonic-like stance with friends including the writer and, later, poet and Aesthetic Realism consultant SHELDON KRANZ (kneeling).

He loved the Marx Brothers and could imitate Groucho very well. He could also make up things to entertain—I remember at a party, his putting on several of the men’s hats, then doing a dance with them on his head, a wild kazatzka.

Hi was an inventive dancer, a lindy-hopper, but he also could glide; I got to be able to follow him and we did love dancing together. He was a pleasure just to watch; it was one of his early hopes to be a dancer, and he trained for a while with the Pearl Primus Company.

Hi and I were different in terms of tempo; we had a big problem with slowness and speed; I often wanted him to hurry as we walked, or when we were going out. Then I found that we saw more when we were walking slowly. At the same time I admired his sense of process, the way he planned a drawing or a print. I was impatient and wanted to see what I did right away; printmaking isn’t like that. I learned about printmaking from Hi and it made me respect the sense of pace, his respect for the techniques that had so much to do with timing.

An important quality about Hi which I admired was that he didn’t gossip. I never heard him tell some story about another artist, nor did he like hearing stories—and this is one of the things that can be so harmful, as everyone knows. Hi was a deep, perceptive critic, and he tried to say what he saw, but he didn’t welcome the chance to have contempt in that way. I think this is one of the reasons people respected him so much.

In 1946 Hi was asked to teach at NYU, and he was proud to use in his classes the chapter on imagination from Eli Siegel’s Self and World. Hi felt the whole teaching of art would get a new dimension when Mr. Siegel’s description of two kinds of imagination—one in behalf of art, and the other against art and life itself—were known. His teaching affected the lives and work of literally thousands of persons. Many times over the years, as Hi and I were in a museum or gallery looking at the work, men and women came up to him, saying: “Mr. Koppelman. I was one of your students. Thank you for what you taught me.”

We Learn about Marriage: The Koppelman Papers

Meanwhile, Hi and I had a lot to make sense of in the aftermath of WWII, and there was turmoil. Happily we had the chance to hear criticism of some wrongly-held notions of love—such as my feeling a man should take care of me while I held myself aloof and painted; and Hi’s thinking a woman should serve him, while he vigorously did his work. This was not a good situation. I thank our fortunate destiny that we were able to study our marriage in Aesthetic Realism lessons with Eli Siegel. We both felt that the anguish of couples which has gone on in America these years would not have been, had they been able to learn what we learned. And I’m proud that dramatic readings of those lessons, called The Koppelman Papers, have been presented on this stage. I am grateful to my colleague and faithful friend, poet Martha Baird, for her presence at the lessons and her editing of those papers.

Mr. Siegel told us, “See your marriage as belonging to art,” and one of the first assignments he gave in order for us to see one another newly was to write a critique of one another’s work. Our excitement about what we saw led us to ask Mr. Siegel in June of 1953 if he would look at and discuss our work critically. He generously said yes.

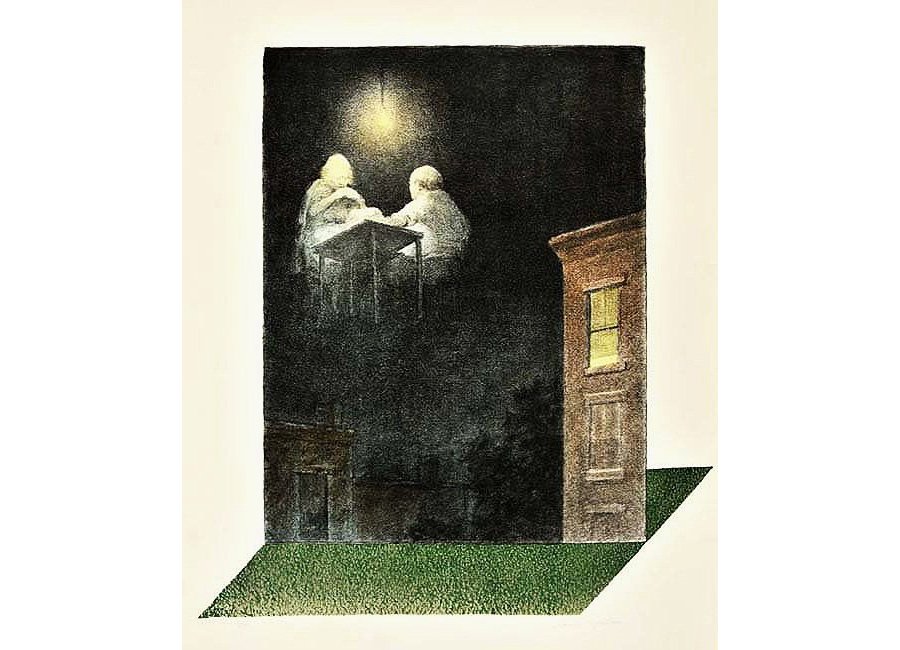

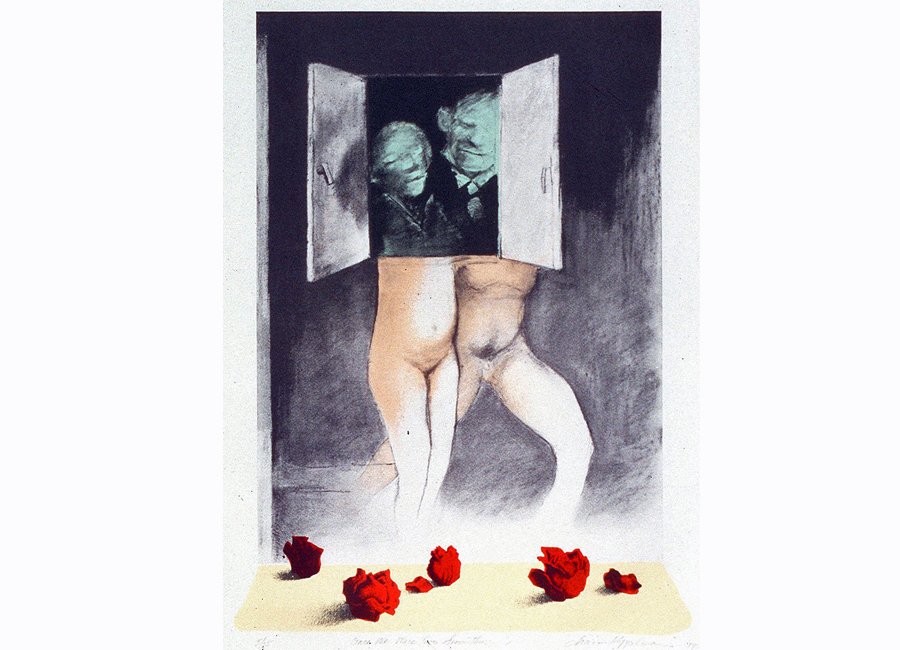

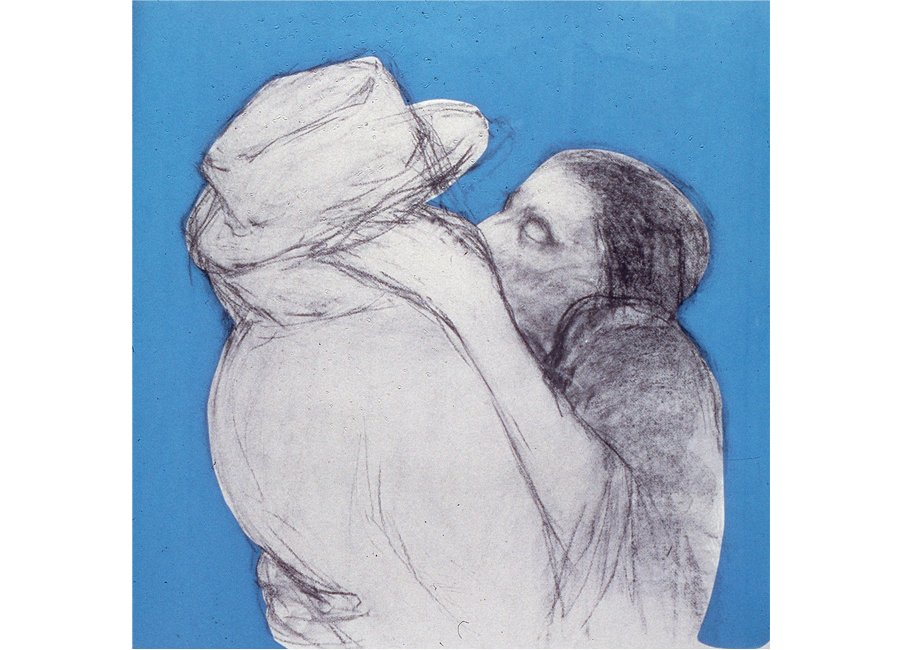

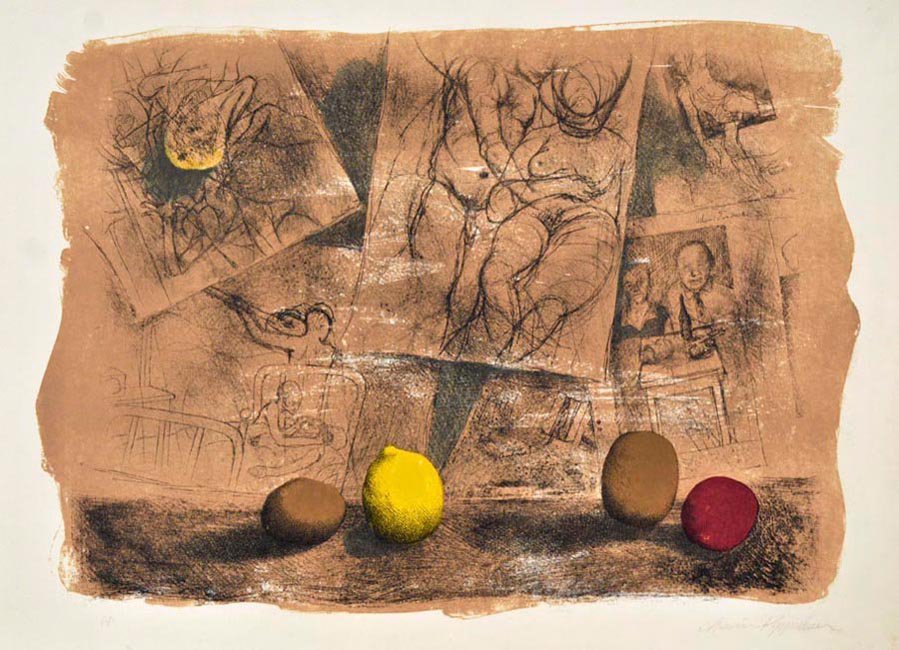

I know I speak for my husband, my fellow artist, when I say that those Art Inquiries showed us new depths in ourselves, and what we were after as artists. Much of Hi’s work is about what he learned and observed going on with couples. His suite of lithographs called Closeness and Clash in Domestic Life shows that. The very title came from Mr. Siegel’s description of the essence of all drama: closeness and clash.

There is a relation of flat greens and domesticity; inner life and vivid reds; of tension and blending, and a fine, tender touch; of individual character and wide surroundings, which in its visual composition has a symbolic and clear message. We need to put together the opposites that are made one in art.

Here is Hi copying Veronese’s Mars and Venus United by Love at the Met—

CHAIM KOPPELMAN copying Veronese’s Mars and Venus United by Love at the Metropolitan Museum, NYC

The Terrain Gallery: A New Dimension in Art Criticism

By the 1950s and 60s other artists came to study Aesthetic Realism. There were the poets Nancy Starrels, Sheldon Kranz, and Louis Dienes, and later the actress Anne Fielding, who brought a new art form, the drama, to the Terrain Gallery. Twelve of us bought a house on 16th Street, the first home of the Terrain Gallery and Definition Press. Here is a picture of Hi just after we put up the sign for the Terrain—

CHAIM KOPPELMAN after putting up Terrain Gallery & Definition Press signs, 1955, 20 W. 16th Street, NYC. Photo by Louis Dienes.

—and he drew notices for our weekly mailings of announcements of various programs. Hi was the print curator of the gallery and he wrote about the opposites in the works of other printmakers. Our study of Aesthetic Realism educated our eyes, widened our tastes. A new dimension has been given to art criticism through Aesthetic Realism. Chaim Koppelman was a forerunner. And I will say more about the Terrain Gallery, and its impact on the art world.

Perhaps the bravest aspect of Hi’s work is in his conscious dealing with human feelings, his own feelings. Hi learned early from Aesthetic Realism and Mr. Siegel that every person had a fight about whether to welcome, to respect the outside world—all art arises from that desire—and the awful hope to have contempt for it. Hi said in the early 60s what he felt should be emblazoned over every art school and studio: “Contempt is the greatest enemy of art, and the greatest enemy of contempt is the Aesthetic Realism of Eli Siegel.”

Here, Chaim Koppelman looks at himself, and asks “Who are you?”—

CONFRONTATION, 1987, color etching (unique proof)

He sees himself as “the ecstatic etcher”—

ECSTASY AT THE PRESS, 1967, ink & sepia wash

Also he looks into his eyes—

THOUGHT (SELF-PORTRAIT), pastel

And in this work Hi shows what he called “the semi” aspect of people, the backing and filling one can have—that is in the early There Is a Way—

THERE IS A WAY, 1956, etching and aquatint

And he can make fun of himself, that is in Voyage—

VOYAGE, 1955, etching

The technique here is so fine: A man with rocks on his head, and they are all in outline, going nowhere. He saw reality’s opposites in the roughness and smoothness of a shape; he felt the drama, as he said, of “black and white” had an ethical equivalent. The largeness of his seeing is in every object he drew.

CONSIDERING OBJECTS, pastel

Napoleon & Us

Over the whole course of Hi’s career there is the presence of Napoleon. Mr. Siegel explained that Napoleon represented the democratic idea, a man of the people, and also something lofty, the emperor. Hi saw that Napoleonic figure as representing himself, both a regular guy and royalty, superior to the masses. He lovingly put Napoleon into that wonderful place, Coney Island—

NAPOLEON ENTERING CONEY ISLAND, 1957, aquatint

And he put three Napoleons on the backs of alligators going slowly forth—

NAPOLEONS ON ALLIGATORS, 1963, etching

Napoleon was a critical presence, looking at him over the press, coming from the workshop walls. Sometimes he is accompanied by an angel, who is often shown at the press with the etcher at work—

NAPOLEON, ANGEL & PRINTMAKER, charcoal

The central oneness of technique and meaning, the combination of criticism and compassion in Hi Koppelman is unparalleled. This was noted by critics and fellow artists, but the source of it was not welcomed by the art world. This brings me to the other fact of our lives—the ugly response, the disastrous silence of many of his fellow artists and of the art press about what Chaim Koppelman loved and valued most: his study of Aesthetic Realism with Eli Siegel.

Anger at Meeting What Is New

The Terrain Gallery made a stir in 1955. We had a point of view that was about more than art—about where art comes from: the whole world and ourselves. We said we were learning from Eli Siegel. Exhibitions were praised, Hi was praised, but our basis, Eli Siegel’s Fifteen Questions about the opposites in art, were, with few exceptions, completely ignored—even while there was a most interesting increase in art reviewers’ use of opposites.

Hi told me about conversations at the various annual dinners among artists when he wanted to talk about what he was seeing, learning. The artists looked scared. Meanwhile, some spoke to him privately, wanting to hear more, including about their own lives, but in public, they were mum.

It was silence born of anger at learning something new from a person not already famous or approved of by the right people. Hi and I ourselves had this unjust anger. We were so wrong—and we regretted it. Meanwhile, decade after decade, Aesthetic Realism and Eli Siegel were boycotted by the press, and Chaim Koppelman was punished because he stood up for what he saw as true and beautiful. But he didn’t betray the honesty he saw and benefited from.

Hi loved Ellen Reiss, the Aesthetic Realism Chair of Education, as I do, and loved studying in her classes. He spoke often about her scholarship and warmth and her integrity in teaching this education as Eli Siegel founded it.

ELLEN REISS teaching the Aesthetic Realism Explanation of Poetry class at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, NYC. Photo by Amy Dienes.

A New Seeing of the World

The magnificent Aesthetic Realism understanding of how contempt hurts people and whole nations can be seen in Chaim’s prints, such as Murdered, Vietnam—

MURDERED, VIETNAM, 1966, embossment/ collage/ soft ground etching

and Board of Directors—

BOARD OF DIRECTORS, 1971, aquatint/collage

It is a wonderful and rare thing that one can find an honest continuity in the work of an artist, a deep and new seeing of the world and oneself. That is what we have in the life and the work of the American artist Chaim Koppelman.

I have gone swiftly over the events of half a century, only giving some memories and crucial high points. My husband was true to something, and I want his colleagues and those persons, artists and others, those who Mr. Siegel called “Dear Unknown Friends,” to learn and celebrate the knowledge that can further honest art and a kind world.